|

PACIFIC ISLAND CULTURE AND SOCIETY

The Papers of Reverence George Brown (1835-1917), Methodist Missionary, from the State Library of New South Wales

Publisher's Note

Robert Louis Stevenson

George Brown (1835-1917) first met Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife on board the SS Lubeck, sailing from Sydney to Tonga, in September 1890. At that point, Brown was the Special Commissioner to Tonga and bound on a tour of inspection. Stevenson was returning to Samoa where he had settled in 1889. It was a time when the Pacific Islands were becoming more familiar to European travellers – Gauguin moved to the French colony of Tahiti in 1891 – but Brown had lived amongst the islanders since 1860 and was an unrivalled source of stories and information about the people and their culture. He was also a regular correspondent of the Zoological Society of London, and knowledgeable about local flora and fauna.

The ship’s smoking room became a popular venue for story telling, as the wife of the Rev J Chalmers recalled:

“Oh! The story-telling of that trip. Did the smoking-room on any other trip ever hear so many yarns? Brown surpassed us all, and the gentle novelist did well. His best stories were personal.”

Brown and Stevenson became firm friends. Stevenson was fascinated by the work, errors and merits of missionaries and determined to write Brown’s life. Sadly, it was a task that he never accomplished, but it is easy to see why he was tempted to do so.

George Brown was born on 7 December 1835 at Barnard Castle, Durham, England. His father, also George Brown, was a self-made man, orphaned at the age of 13, but who worked hard to achieve success as a lawyer, newspaper editor (founder of the Darlington and Stockton Times), Unitarian preacher and local worthy. His mother, Elizabeth Brown (née Dixon), was born into the Church. Her father was a leading member of the local Methodist Church and one of her sisters married the Rev Thomas Buddle, a missionary in New Zealand. Another sister lived in Canada. George’s mother died when he was only five years old, and he never came to terms with his disciplinarian step-mother.

George was sent to a small private school and had “what used to be reckoned in that little town a good education … , but I am sure it would [now] be considered wretchedly bad….” On leaving school he attempted a number of different jobs. His role as an assistant in a Doctor’s surgery was terminated “after nearly blowing up the establishment in trying to make hydrogen gas” and he was bored when working at a chemist’s shop and then a bonded warehouse in Sunderland. He had more joy when apprenticed to a draper in Hartlepool. This was mainly due to the fact that they did a great deal of business with the captains of foreign ships, whom he had the opportunity to meet. He was soon involved in the smuggling of contraband on and off the ships, exchanging moleskin and print goods in exchange for cigars, tobacco and other dutiable goods, all with the approval of his employer, but without the knowledge of the customs authorities.

At Christmas 1851, he borrowed 10 shillings from the draper and ran away to sea. After travelling to Newcastle, he used his money to buy a steerage passage on the City of Hamburg to London, where he hoped to find employment on a larger ship. He was first engaged as a ship’s cook on board the Savage, but jumped ship when he realised he could not make a plum duff. He was then taken on as an ordinary crew member of the Alice, bound for Algoa Bay, but was intercepted by lawyers acting on behalf of his father. They soon realised that his heart was set on a life at sea and they could not convince him to come home, so his father paid for suitable clothes and his uncle found him a place on a troopship under the command of one of his friends.

The Santipore was a former East Indiaman and it made heavy weather of the passage from London to Ireland to pick up troops. Young George was shown no favours and took his place hauling ropes and in the topsails like anyone else. The hardships did not put him off and the voyage to the Mediterranean made a deep impression on him – especially the sight of the fleet assembled off Malta for the inspection of Admiral Dundas. He visited Corfu and Gibraltar and then made a transatlantic voyage to Quebec with the 26th Cameronians. He then had two near death experiences that changed his life. Firstly, he fell from a ladder while climbing from the lower hold and was only saved by landing on a hatchway, breaking his leg. Secondly, on account of this, he missed the onward voyage of the Santipore, which shortly afterwards went down with all hands.

George Brown convalesced at the Marine Hospital in Quebec and then set off on a journey of self-discovery in Canada. He spent some time with the Cameronians in their barracks in Montreal and then worked the Lakes on a cargo steamer called the Reindeer. Eventually he found his way to New London, Ontario, where his mother’s eldest sister lived, and he was given a job as an assistant in a general store. This could have provided the platform for a mercantile career – and he was given the opportunity to manage a store in Michigan – but a failed love affair and an altercation with a fellow employee caused him to move on again. He sailed for home.

He worked his way home as a crew member of the Olive, bound for Bristol. It was a rough passage and a rough crew, and they nearly came to grief off Lundy Island in the Bristol Channel. He returned to the north-east and his father must have hoped that he would settle down. But he turned down a place in his father’s offices and resolved to travel to New Zealand – “simply because it was the farthest place from England.” It was also the home of his missionary uncle, the Rev Thomas Buddle, and his mother’s sister.

His father consented, provided he travelled as a passenger, and so he set off in March 1855, at the age of 19, on board the Duke of Portland, with Bishop Selwyn of New Zealand, the Rev J C Patteson (later Bishop of Melanesia) and the Rev Carter as company. It was a long voyage and he passed some of the time attending Bishop Selwyn’s Bible classes and learning Maori.

On arrival in Auckland he made his way to his uncle and aunt’s house in Onehunga, where he received a very warm welcome. Even though he found a job and accommodation in Auckland, he spent much time with his relations and “experienced the power of sermons which were never spoken or preached at me.” As a result, he joined the Bible classes of the Rev J H Fletcher at Wesley College, Auckland, which he remembered fondly for the rest of his life. This led him to work for the YMCA and as a local preacher. He then fell under the influence of the Rev R B Lyth, a veteran missionary, who encouraged him to spread the word in Fiji. With the help of the Rev Isaac Harding, superintendent of the Auckland circuit, he was accepted in 1860 as a Methodist missionary, with a posting to Samoa. Matters then proceeded with great haste. He resolved at once to secure “a suitable helpmeet” and set off on pony to Whaingaroa “where the young lady was living whom I had long thought to be best qualified for that position.” Consent was given and on 2 August 1860 at Raglan, he married Sarah Lydia Wallis, daughter of the Rev James Wallis, another experienced missionary. Their honeymoon was spent on an arduous and extremely muddy six-day trek through the bush to Waikato and on to Onehunga in time to catch their passage to Sydney. On several occasions they had to swim across harbours with their horses. They received great kindness from Maoris along the way.

George and Sarah Brown left Auckland for Sydney on board the steamer Prince Alfred on 4 September 1860. During the five-day voyage, Brown read the chastening missionary memoir of Richard Williams, who joined Captain Gardiner on his mission to Tierra del Fuego. All members of Gardiner’s party died of starvation as they depended “for their subsistence on fish they were not able to catch, and on birds they had no ammunition to shoot.”

The Rev George Brown was ordained in the York Street Church, Sydney on 19 September 1860 by the Revs J Eggleston, (President), S Rabone, S Ironside and T Adams, and on 26 September he and his wife set sail for Samoa on the John Wesley. After a brief sojourn in Tonga they arrived in Samoa on 30 October.

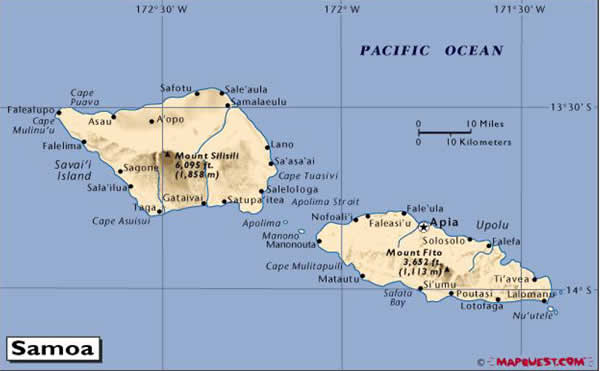

From 1860 to 1874 he was resident in Samoa, learning the language and recording whatever he could of Samoan culture. As with his later mission stations, he showed real empathy toward the indigenous peoples, regarding them as friends, and spent much of his time exploring the interior of the islands. He spent most of his time on Savai’i, the largest of the islands with a circumference of about 250 miles, but he also braved the coral reefs and unpredictable seas in small canoes in order to visit the surrounding islands. There were few good landing places and it was always perilous.

Please click here for a map of Samoa

The first Methodist missionaries had arrived in Samoa in 1828, so the mission was well established and there were several thousand professed Christians. Savai’i was divided into districts, comprising a handful of villages, to each of which a teacher was appointed, one of whom was made the catechist, or local superintendent. The teachers all gathered once a year to discuss matters of policy, administration or discipline. Brown also made regular visitations of his Circuit, taking five to seven weeks at a time to accomplish this. This gave him ample opportunity to observe the flora and fauna of the islands, as well as the customs and habits of the people.

It was in Samoa that he commenced his manuscript journals. Ten substantial volumes survive, giving a first hand account of his missionary experiences, 1860-1871, 1874-1880, 1888-1890 and 1897. These start in November 1860 when he announces his intentions:

“Having decided that I ought to do justice to myself and the Missionary Society by whom I am sent out [I decided] to keep some record of any events which may take place during my stay. I think it best to commence by a short outline of our proceedings since we said farewell to our kind friends in Auckland and started on our journey to this place.”

The journals proceed with a detailed account of life on the Pacific Islands, revealing his interest in landscape, folk tales and local beliefs. He found the people “to be amongst the nicest and most lovable people with whom I have ever lived.”

For the first two years they lived in a bamboo house with earthen floors in Satupa’itea, Savai’i. It was both damp and exposed to the elements. So they embarked on the building of a proper mission house, burning coral for lime, gathering quantities of stone and cutting down large trees in the interior and dragging them to the coast. It would not have been possible without the unpaid labour of many of his local flock. Brown acted mainly as supervisor and surveyor and also made the frames into which the concrete was poured.

His mission work was varied between education, evangelism and medicine as is shown by a typical diary entry of 10 May 1861:

“Held our [religious meeting] in the open air. About 300 were present. The Chief commenced this their first Collection in their own village by a subscription of $10 thrown into the plate in such a manner as to let every one know what he gave. Others then followed many of them giving $2 each. We thus realised $122.72. Administered Medicine to about 130, a very tiring and fatiguing affair. In the evening we held service and gave an address on the necessity of repentance….”

He also had plenty of time for exploration and the diaries are full of detailed observations. For instance, in 1864 he writes:

“There are many plants and trees inland that the Natives do not know at all. One which I found near the mountain but did not see anywhere else is very beautiful indeed – it has a large white flower and looks very pretty amongst all the black stones. I was very much struck with the evident marks of the goodness and wisdom of God manifested in the wise provision He makes for supplying the wants of people. On the Beach the Cocoa Nut supplies drink for all, but here there are none and but little water. However there is an abundance of a species of vine … and we had only to cut one with a knife then put the severed end to the mouth, make another division a little higher up to serve as a vent and then drink as fast as possible. From a piece about 18 inches long about a tumbler full of fine clear water can easily be obtained.”

There are descriptions of the idyllic lifestyle on Savai’i, a fertile and mountainous island dominated by Mt Silisili and well provided with coconuts, bananas, breadfruit trees and pigs, where people fashioned clothing from bark-cloth and matting from the coconut trees.

From the 26th to the 27th January 1865 he experienced the might of a hurricane, including the brief calm brought about by the inner eye of the storm and the sudden change in wind direction.

Violence of a different sort was supplied by the villagers who “were extremely sensitive to what was considered to be an insult.” According to a local proverb, “Stones decay, but words never decay”, so feuds continued for generations. Between July and September 1866, war broke out between the people of Satupai’tea and Tufu and at least six men were killed and many injured. Brown returned from a tour of his Circuit to find the violence and tried to make peace. He took advantage of a local custom by sitting down on the main pathway between the two villages. When the warriors from Tufu approached they could not pass, as it was considered ‘malaia’ (unfortunate) to pass or trample upon those making peace. He describes the scene:

“On they came, a band of stalwart fellows, almost naked, brandishing their guns, spears, and clubs, leaping and shouting, to the place where we were sitting. Their bodies were smeared with oil, their hair dressed with scarlet flowers, and their foreheads bound with frontlets made of the bright inner shell of the nautilus. It was difficult to recognise the features of those with whom we were acquainted, as every one had tried to make himself as hideous as possible. The chief led the way, dancing up to us, and shouting: ‘What is that for?’ ‘Why are you sitting there?’ ‘Why do you stop us?’”

Brown and his colleagues remained seated all day until an uneasy truce was declared. Trouble flared up again in late August 1869 when the allied forces of Tufu and Palauli took possession of the inland plantations of Satupai’tea and prepared to attack the town. Once again Brown attempted to mediate a peace, but his efforts were interrupted by gunshots and a brutal battle ensued. Brown managed to make his way back to the Mission house where he found the grounds “full of women and children, and all the old and sick.” He noted that the women were praying earnestly to God. The warriors from Palauli took one end of the village and burnt it down, but they were outflanked by men from Satupai’tea in a double-canoe and forced to retreat. The people of Satupai’tea were still heavily outnumbered and Brown persuaded them all to leave the village under cover of night. In the morning of the 31st he told the Palauli and Tofu that everyone had gone and begged them not to burn the abandoned huts or destroy the trees on the beach. They consented. Ten men had been killed on each side, including the chief of Satupai’tea. The town was abandoned and Brown relocated to Saleaula on the north-east coast.

There were other rivalries as well, including those between missionaries. This can best be illustrated by a tale about the Palolo, a foot long marine worm that suddenly appears in small groups off the coast of Samoa one day late in October, becomes abundant the day after, and then disappears. The Samoans regard it as a delicacy and a gala feast was arranged each year to mark the harvest of the worm. Brown recorded both the nature of the worm and the attendant festivities in his writings and he kept careful records so that he could predict its annual appearance. The Samoans used the stars and the phases of the moon to foretell its coming. One year they asked Brown for his opinion on when it would appear and they were dismayed when he concurred that the major efflorescence would be on a Sunday – the day of rest. While they struggled with their conscience over this they were tempted by a group of Roman Catholic visitors who assured them that God sent the palolo and they were intended to be harvested regardless of the day. Notwithstanding their assurances, on the Sunday it was mainly the visitors who harvested the worms. The villagers were further tempted when the palolo were brought by the visitors to a feast held the day after. No one knew whether to eat the palolo or not. Then a local preacher recalled Paul’s Epistle to the Corinthians (Chapter 10, verse 27): “If any of them that believe not bid you to a feast, and ye be disposed to go; whatsoever is set before you, eat, asking no question for conscience sake.” Much relieved, they all tucked in. Apart from reminding us that missionaries did not always act in isolation, Brown was also pleased that the story revealed the Samoan’s close knowledge of the scriptures.

After fourteen years in Samoa, the Browns decided to leave the islands in 1874. Lydia Brown wanted some time in a more settled environment to raise their growing family (much heartbreak had already been occasioned when two of their daughters were sent away to school in New Zealand). George Brown wanted a new challenge and fancied the task of establishing a wholly new mission in New Britain, New Ireland, and the Admiralty Islands - part of the Bismarck Archipelago, which now forms part of Papua New Guinea. They sailed for Sydney and Brown pitched his proposal to the Executive Committee of Missions of the Australasian Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society on 9 September 1874.

The area he was proposing to evangelise was not for the faint hearted. Government officials spoke of “the people – that they were great cannibals and very fierce; that the islands were very unhealthy, so that almost everyone who went there suffered from fever and ague; [and] that food might be very scarce….” Brown was undeterred and the Committee approved the Mission provided that he undertake a feasibility survey, visit the proposed territories and raise funds.

For three months he travelled across New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania canvassing support, obtaining particularly valuable help from Henry Reed of Launceston. In January 1875 he visited New Zealand as well and settled his family in Auckland. On 27 April 1875 he boarded the John Wesley once again, this time bound for Fiji, Samoa and New Britain.

Please click here for a map of Papua New Guinea

Amongst his fellow passengers were the Rev Lorimer Fison (1832-1907), the Wesleyan missionary and anthropologist, and his family; the Rev Jesse Carey and his family; and Baron Anatole von Hugel (1854-1928), the young naturalist who later became the Curator of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge. They arrived in Fiji on 16 May 1875, in the aftermath of a measles epidemic that had killed over 40,000 of the islanders. They witnessed dreadful scenes across the island with many of the dead still awaiting burial and they were impressed with the work of the local volunteer missionaries.

Brown left Fiji on 15 June and took with him a number of native Fijian teachers who had volunteered to join his new mission, together with Walter, a photographer, and Jack, a seaman from the John Wesley, who had offered to help him. They arrived in Samoa on 30 June 1875 and Brown was able to take on board two Samoan teachers and their wives as well as two of his old boys. They then sailed for New Britain via Rotuma.

They arrived in St George’s Channel, between New Britain and New Ireland at around 1pm on 14 August 1875. By 8pm canoes drew up to their boat and a number of natives came on board to trade: “They were quite naked, and not at all prepossessing.” The next day they anchored at Port Hunter, Duke of York Island, where Captain Ferguson recommended that they should establish their first mission station. Another group of natives came on board including Topulu (alias King Dick), who was to become an important part of the mission, frequently employed as a translator. Brown’s Fijian and Samoan colleagues were still quite nervous and Brown decided that he could not sail off and leave them. Instead, he resolved to stay for a year and commenced building a mission station house on a high piece of land above Port Hunter, which he bought from Topulu with “a properly executed conveyance.” On 9 September 1875, Captain Ferguson sailed off on the John Wesley and Brown was left to explore his new domain. Walter, the photographer, also departed, but sold Brown his camera and equipment.

Despite the fact that Dampier had named New Britain in 1700, very little was known of this island or of any of the other islands making up what was called the Bismarck Archipelago from 1884 onwards (covering c19,200 square miles and including New Britain, New Ireland, the Duke of York group, New Hanover or Lavongai, Sandwich, Gerrit Denys, St John’s, Sir Charles Hardy’s, Fischer Islands and the Kaan group). A few traders had visited Port Hunter and Matupit, but none had stayed for long.

The climate was tolerable – with temperatures ranging from 78° to 90° - but there was great humidity. They were pleased to find a rich variety of plant life including palms, ferns, orchids, bamboos, rattans, paper mulberry, ginger, turmeric, arrowroot, coconut, ‘kava’ root, yams, taro, sweet potatoes, mango and bananas. Brown planted orange, lemon, lime, custard, apple, guava and Chinese banana trees, and all thrived. Animals on the islands included wallabies, cuscus, bandicoot, flying phalanger, wild pig and a species of dingo. Snakes and lizards were also very common, but none were found to be venomous. Brown’s studies of the flora and fauna were extensive and he sent his findings (and many specimens) to the London Zoological Society (these were published in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society, 1877-81).

He first went to New Ireland on 5 October 1875, but was warned not to do so by the natives on the Duke of York Islands who told him that he would be killed. To his surprise, he found the people at Batigoro to be very friendly and with the help of Waruwarum from Port Hunter (his translator), he was able to trade with them and discuss the opening of a mission. Given that the goods on New Ireland were cheaper and more plentiful than on the Duke of York Islands, he did wonder whether the warnings were just a ruse to prevent commercial contact with a rival.

On 12 October 1875 the first mission station was opened on New Britain at Nodup, at the request of Tobula, a chief of that village. A house was built and paid for and two of the Polynesian teachers stayed behind. Brown next visited Matupit in Blanche Bay and faced a near mutiny on his steamer. Once again, the Duke of York islanders were sure that he would be eaten. Once again, he managed to trade successfully with the locals and found them to be friendly. However, he did find clear evidence of cannibalism within their huts and many of the chiefs spoke openly of gaining vengeance on nearby tribes by taking captives and eating them. By November, a teacher had been placed on Matupit and three in Kalil, New Ireland. He wrote in his diary:

“No mission could have had a more promising beginning than ours has had in all these islands. I believe that our principle difficulties in the future will arise from the great difference between the dialects, the constant feuds between the villages, and the want of authority among the chiefs. But as our knowledge of language increases, we shall no doubt be able to decrease very much the number of dialects as we introduce the use of books in our schools; and the reception of the religion of Jesus will soon produce peace and order where all is now discord and confusion.”

Brown continued to explore the islands and sailed up the coast of New Britain as far as Cape Palliser. He was surprised at the number of isolated tribes that existed and – as noted above – the dialect differences. He delighted in bringing the peoples together: “We take a few chiefs with us every time we go out, and so they are compelled to go to places where they would never have dared to go in their own canoes. They meet chiefs there, and instead of enemies, find friends….”

The first church was opened in Port Hunter on 28 January 1876. It would not have been possible without local labour, which was provided for free. This was an important point of principle for Brown, who wanted the locals to know that “ the church was theirs, and not mine.” It also gave them a feeling of genuine ownership and belonging.

In February 1876 he received a visit from Captain Hernsheim of the Coeran, and used the opportunity to visit Spacious Bay. This was too far for him to make a return journey on his steam launch, so Hernsheim towed him there and left him to make his own way home. The local people were not used to receiving visitors, as he noted in his diary:

“Friday, February 11. Early this morning we saw the natives, as several canoes came near the ship, but we had very great difficulty indeed to persuade any of them to come alongside. We threw beads and pieces of red cloth, which they eagerly seized, but they were still very shy. The general impression with us was that they had rarely, if ever, seen a vessel before. It is not at all a likely place for any vessel to go to, as it is quite out of the track, and we could not see the slightest sign to indicate that they had received any articles of trade before. They were quite ignorant of tobacco, and wouldn’t take it at all for barter. … It was at once evident that these people differ considerably from any we had yet seen. They are lighter in colour, their hair is finer and not so matted as the natives farther north, and altogether they appear to be a finer race. This was especially noticeable in the case of the women, many of whom seemd like the Eastern Polynesians – in fact, some of the girls were not much unlike Samoans. … the women here occupy a much higher social position….”

Other women on the islands were less lucky and one of the local practices that Brown records is ‘tabusiga’, or the custom of keeping young girls in darkness and seclusion from the onset of puberty until they are marriageable. For this purpose they had a large house, about 25 feet in length, containing three conical structures which were about 7 or 8 feet tall and 10 or 12 feet in circumference at the bottom and for about the first 4 feet up. These ‘cages’ were covered with the broad leaves of the pandanu plant, so that no light can enter. Each contained a young girl who had to stay in seclusion for up to 5 years. They were only allowed out of the cages once a day to wash, but still within the confines of the house, which was ‘tabu’ (forbidden) to all men. This custom was mainly followed by the poorer villagers who could not afford the alternative of an expensive feast.

On 18 March 1876 they opened the first church in New Ireland, followed by a feast to which Brown donated a pig. The congregation were delighted with the translation of one of the hymns into their own language and enjoyed the food. By this process of trading, establishing friendships, holding meetings, hosting feasts, and learning and using the local language, Brown and his fellow missionaries were able to build up their following. Brown was encouraged:

“There is certainly a great field of work: the population is large, and the people are accessible. With ordinary precautions there is no great danger in visiting them. True, they are all cannibals and continually at war with each other, but they are not fierce, and I believe that they will not readily attack a white man.”

Only one of the original 10 teachers who arrived with Brown died during the first year – and he of ill health. As new teachers arrived, Brown made plans for 16 mission stations across the archipelago and he felt confident enough to leave these in the hands of his Fijian and Samoan colleagues, whilst he reported back to Mission Headquarters. Brown left Port Hunter on the John Wesley on 31 August 1876 and arrived back in Sydney on 10 October.

The Wesleyan Board of Missions reviewed his findings carefully and enthusiastically endorsed the future continuation of the mission. Henry Reed continued his generous support with a pledge of £200pa. By the 30th October, Brown was able to rejoin his wife and children in Auckland. Lydia agreed to join him on his return to the islands, although it was agreed that five of their children should remain in New Zealand for the benefit of their health and education. A large wooden house was pre-fabricated for them in Sydney and put on board the John Wesley, on which they sailed on 18 May 1877, together with a carpenter, Mr McGrath.

They sailed via Fiji and Rotuma and arrived in Port Hunter on 21 August 1877. Brown was saddened to find that there had been a great deal of illness on the island while he had been away and one teacher, two teacher’s wives and two children had died. He was also saddened to find that only three of the proposed mission stations had been set up. The remaining native ministers and teachers had set up “a little village of their own” in Port Hunter. Brown quickly set them to work. Some helped McGrath to construct his new house. Others started to establish the new stations starting with one on the North-west coast of Matupit in Kabakada, where a trading station had recently been set up by “Messrs Southwell and Petherick, who were trading for Messrs Goddefroy.” Another mission was situated at Ratavul, where another trader, Mr Brunow, had settled. By 9 October there were 7 stations on the Duke of York islands, 11 on New Britain and 5 in New Ireland.

The visit of the ketch Star of the East in January 1878, with a party that included Mr Turner of the Sydney Botanical Gardens, prompted a second expedition to Spacious Bay. They identified the first eucalypts known to grow in New Britain, collected samples of gum, seeds and flowers, and Brown shot many specimens for his burgeoning natural history collection. His scientific work increased during this period and many critics claimed that he was more interested in naming snakes, birds and insects than saving souls. Given the rapid spread of mission stations this seems unjust – in any case the scientific and ethnographic evidence that he gathered is now very valuable.

On 30 January 1878 a series of major volcanic eruptions took place on the islands. Brown was lying ill in bed when it started and was not able to visit the site of the eruptions until mid-February. He noted that some sections of the sea-bed had been raised and there were large quantities of pumice all around, some of which were swept out to sea. He encountered vents of sulphurous steam and a crater lake full of boiling water.

On 5 March 1878 they celebrated the first marriage in the group, between Peni Luvu, one of the pioneers, and Lavinia, the widow of Aminiasi. However, their joy was short-lived. A wave of illness went across the islands incapacitating most of the missionaries. Then, in April 1878, a group of islanders attacked, killed and ate the Rev Sailasa Naucukidi and three teachers (including Peni Luvu) while they were travelling inland in New Britain. Taleli, a local warrior, was said to have ordered the killings.

The ‘Blanche Bay Affair’ – as it was to become known – hinged on the response of Brown, his missionary colleagues and the traders, to the unprovoked attack.

Brown first heard about the massacre on 8 April 1878 from Kail, a native. He didn’t give the story much credence at first, but it was confirmed to him the next day and on 11 April he visited Sailasa’s house in Kabakada, where he found the terrified widows and children of the deceased. They were removed to Port Hunter and on 13 April Brown called a meeting of the white residents, together with the native teachers and some of the chiefs, to decide what course of action to pursue. It was agreed that all of them were in imminent danger and there was a real possibility of a major uprising by the islanders. He was urged to take reprisals and had to act swiftly or face the possibility of unilateral action being taken by some of the parties. He agreed reluctantly:

“I determined that as some action was unavoidable, even if not desirable, it was the best plan to enlist the sympathies and help of all the well-disposed natives on our side, rather than to array them against us; and let the punishment of the murderers come from the natives as much as from us. The murder of Sailasa and the teachers, it must always be remembered, was not in any way connected with their position as Christian teachers, nor was it caused by any enmity against the lotu. They were killed simply because they were foreigners, and the natives who killed them did so for no other reason than their desire to eat them, and to get the little property they had with them.”

They set forth on 16 April. On landing in New Britain they split into two parties with Mr Hicks leading a party that included Messrs Powell, Turner, McGrath, Knowles, 10 Fijian and 4 Samoan teachers and natives from Nodup, Matupit and Malakuna; and Brown leading a smaller party of Messrs Blohm and Young, with one Samoan teacher. Brown’s party was to circle round to the North coast and gain support from the natives there, and Hicks was to march directly on the villages that had been involved.

Brown’s party of four found themselves in a severe predicament. Whilst they were talking with Chief Bulilalai and a group of about 500 supposedly friendly natives on a northern beach, they found that their retreat had been cut off by some 40 canoes, each containing four to eight men. They quickly got back into their own boats and drove off the menacing canoes. This impressed Bulilalai and his men who went into the bush and fought Taleli’s people. Brown and his colleagues went along the coast to Taleli’s house and burnt it, also destroying his canoe.

Hicks’s party travelled into the interior of New Britain by moonlight and attacked a series of villages implicated in the massacre at dawn. They burnt down all the huts and some of the murderers were killed. The official death toll was ten, but none of Brown or Hicks’s party were seriously hurt.

On 21 April Brown recovered some of the bones of the murdered teachers and on the 23rd they raided the village of Diwaon, where Sailasa and his colleagues had been killed. Brown took charge of the boats, while the raiding party torched the village.

The swift action brought about an immediate response and Brown started to receive offers of diwara (shell money) from local tribes who wished to become friends again. They acknowledged that islanders had started the trouble and that the action taken had been fair. Relations between the islanders and the missionaries improved dramatically and Brown felt safe wherever he went. In a letter to the General Secretary of the Missionary Society he wrote:

“The effect, I am certain, has been most beneficial, and in this conviction all the foreign residents here concur. I am certain that our Mission here stands better with the natives than it did before, and that we are in a better position to do them good. They respect us more than they did, and as they all acknowledge the justice of our cause they bear us no ill will. Human life is safe here now for many years to come.”

The Australian Press were less kind in their opinions and both The Weekly Advocate and The Age carried fierce criticism of the affair. The Australian, slightly more temperate in its views, said:

“If missionary enterprise in such an island as this leads to wars of vengeance, which may readily develop into wars of extermination, the question may be raised whether it may not be better to withdraw the Mission from savages who show so little appreciation of its benefits.”

However, Brown was ably defended in the press by the veteran missionary, the Rev B Chapman, and received letters of support from the Imperial German Consul for the region and from the Missionary Society. Brown continued with his work.

On 2 December 1878 the John Wesley arrived at Port Hunter and the Revs Danks and Watsford came ashore to conduct an impartial review of the work of the mission. Watsford concluded that the mission was not over-extended and that the natives were now friendly and peaceable. Danks stayed behind and joined the mission.

Brown became ill early in 1879 and the situation became critical by the end of April. On 1 May 1879 he agreed to take passage on the steam launch Alice, bound for Cooktown, but he had to leave his wife and three children behind due to space constraints. After a brief period of recuperation he went on from Cooktown to Brisbane and then on to Sydney where he arrived in May 1879. He collapsed while giving an address at Bourke Street Church and was told rest further, which he refused to do. Even when he was told that he was sure to die, he rejected the advice, convinced that he still had work to do. But he then went to Auckland and spent two months with the five children that they had left behind.

On 18 September he set sail again on the John Wesley, arriving in Tonga on 4 October. After a month there (where the Deputation that sailed with him had work to do) they sailed for Fiji, arriving there on 3 November. He didn’t expect to stay there for long but found himself at the centre of a Government Inquiry and then (on 13 November) facing criminal charges relating to the Blanche Bay Affair. In both cases he was fully exonerated.

He left Fiji on 15 November and the John Wesley was initially becalmed. They made very slow progress and did not pass the island of Tucopia until 6 December. Then the wind picked up – and how. It turned into a hurricane and the ship was within moments of sinking when the captain and his crew cut down the mainmast to save it. By 9 December the storm had passed and they surveyed the ship with its fallen masts and wrecked rigging. The ship’s carpenter fashioned two small staysails and erected a new topmast and they hobbled backed to Sydney on 23 January. Brown was annoyed that the Captain had not been able to drop him off in the Solomon Islands as he had promised, especially when he received the tragic news that his young son, Wallis, had died on 12 October and another of his children and Mrs Danks were seriously ill.

It was not until 13 February 1880 that he was able to leave Sydney on board the Avoca and they had a lengthy sojourn in Marau, where he had to fill his time collecting natural history specimens. They also stopped at Cape Marsh and New Georgia in the Solomons and Brown carried out some ethnographical and linguistic work with the fearsome Ruviana people (“the Vikings of the Solomons”). They finally arrived at Port Hunter on 21 March 1880, where he received the news that his daughter, Mabel, had died on the 12th and his wife had gone with their son, Geoffrey, and the Rev and Mrs Danks to New Britain. She could no longer bear to live in the house at Port Hunter. With the help of his good friend Captain Ferguson, he found his wife the next day in Kabakada where they wept together for a long while.

His third term of residence in the Bismarck Archipelago was not a particularly happy one. They had to deal with the sorry aftermath of a French colony that had been established near Cape Bougainville, New Ireland, in January 1880, but failed and many of the colonists became extremely sick. Brown described the attempted colony as a “mad scheme” and wrote:

“They have begun the venture without having any proper conception of the nature of the work, or the difficulties to be encountered. No good judgment whatever has been exercised as to the suitability of the place, which seems to have been selected in some drawing-room in France, whilst looking over an old book of Bougainville’s travels.”

The survivors were brought to Port Hunter and Brown and his wife nursed most back to health. They were eventually shipped off to Sydney in September.

Brown also learnt of the death of Captain Ferguson, whose ship, the Ripple, had been attacked on 9 August 1880, by a group of about 300 natives in canoes off Bougainville Island. The natives boarded his vessel and he was one of four casualties on the Ripple, before the invaders were driven off by musket fire. Brown helped to get a memorial erected to his friend’s memory at Nusa Songa in the Solomon Islands.

The mission continued to expand. The first local preachers were appointed on 13 April 1880, chosen from amongst the many converts on the islands. Brown later said that it was one of his greatest joys to hear native preachers spreading the word to their fellow islanders in their own language. A new church was built at Kalil in New Ireland and this was opened on 17 June. Another, larger church in Molot was often crammed full and the number of baptisms rose considerably. By October 1880 there were 29 mission stations in the archipelago and Lieutenant de Hoghton of HMS Beagle declared “it is my decided opinion that the Mission is doing unmixed good wherever its influence is felt.”

After 4 years serving in the Bismarck archipelago (Aug 1875 – Aug 1876; Aug 1877 - May 1879; Mar 1880 – Jan 1881), the Browns returned to Australia. They set sail for Sydney on 4 January 1881 on board the schooner John Hunt and arrived there on 2 February, just in time for Brown to address the local mission conference, where he received a very warm welcome. He brought with him a native of New Britain called Timot, who helped him to translate the gospels into the languages and dialects of New Britain. At the main mission conference in May, Brown was once again exonerated for his actions in the Blanche Bay Affair.

On 10 September 1881 the Rev B Chapman, General Secretary of the Wesleyan Missionary Society, died and Brown agreed to help the President of the Society to conduct office affairs. He also carried out local deputation work and wrote a noted series of articles for the Sydney Morning Herald known as the ‘Carpe Diem letters’ (1883-85). These openly criticised the lack of urgency in British policy in the Pacific and warned of German ambitions in the area. In 1883 he was appointed as second minister to the Bourke Street Circuit. The following year he was made Superintendent of the Circuit, which post he held until 1886. During 1886 he paid his first return visit to England, taking a scenic trip via San Francisco and America. It was a long trip and he spoke to Methodist assemblies all over Britain, including the Conference Missionary Meeting in Great Queen Street Church, London. He also acted as Commissioner for New South Wales at the Indian and Colonial Exhibition in London. He returned home in 1887 by way of Montreal and the Canadian Pacific railway. After so long in the tropics, thick snow and temperatures of -49° were a novelty to him. On his return he found that he had been appointed General Secretary of the Wesleyan Board of Missions. He took over this office on 7 April 1887 and held it until his retirement in April 1908. It gave him the opportunity to formulate and influence missions’ policy in the Pacific and to travel widely across the region.

Within a very short time Brown was summoned to Tonga where a political and religious crisis had been brewing since the ratification of a new Tongan constitution in 1875. This constitution had been drafted in part by the Rev Shirley Baker. He was a Wesleyan missionary who had acquired the confidence of King George Tubou, ruler of Tonga, and sought to make the islands a strong and independent kingdom. The British were alarmed when he negotiated a treaty with Germany in 1876 and, even though they signed their own treaty in 1879, they put pressure on the Wesleyan Board of Missions to have Baker recalled so that his influence could be checked. The Mission Board did not wish to enter the political arena, but recognised that Baker’s actions were compromising their work and Baker was brought back to Auckland. However, when the Crown Prince and Premier of Tonga, Tevita ‘Unga, died unexpectedly, Baker returned to Tonga and accepted King George’s offer to be Premier. He formally resigned from the Wesleyan Board of Missions in 1881 and, annoyed by the way he had been treated and in line with his views on independence, he sought to establish an independent church in Tonga. Worse was to come – in January 1887 a group of Wesleyans were implicated in an attempted assassination on Baker. In consequence, 6 men were shot, and Baker commenced a policy of confiscating the property of Wesleyans and others, and sending them into enforced exile without trial.

Brown arrived in July 1887 and had friendly meetings with all of the main parties during his brief stay. He recommended a consensual approach, reuniting the Wesleyan Church of Tonga with the new Free Church, and giving it a degree of autonomy. He also proposed the recall from Tonga of the Rev J E Moulton, a prominent Wesleyan missionary on the island, who clashed strongly with Baker. Notwithstanding this at the 1888 Mission Conference it was Moulton who proposed that Brown should be appointed Special Commissioner to Tonga, to shepherd the Wesleyans who remained and to find a peaceful solution to the crisis. Brown accepted the appointment and left for Tonga again on 23 July 1888. He continued to meet with Baker, King George and Sir J B Thurston, Governor of Fiji, who was an old friend. As a result of this quiet diplomacy, King George became less in thrall to Baker and the British authorities became more pro-active. Brown returned to Australia on 19 December, 1888, to discuss matters with the Tongan Committee. He sailed back to Tonga in April 1889 and travelled about the islands continuously until October that year documenting the wrongs that had been done to the Wesleyans in Tonga. This prompted Baker to write a number of “mendacious and slanderous” letters concerning Brown, which only served to anger British authorities and drive a wedge between Baker and King George.

Brown returned to Sydney via Fiji (and another meeting with Thurston) in November 1889 and submitted a report that was discussed at the Mission Conference in May 1890 detailing the injustices done to the missionaries and stating that he had lost all hope of effecting the necessary reforms and restitution through the Premier. This finally provoked Sir James Thurston to visit Tonga for a meeting with King George Tubou, after which Baker was dismissed and, from 17 July 1890, he was banned from the islands. Freedom of worship was restored, the untried exiles were recalled and confiscated lands were given back. His last major visit to Tonga was in September 1890, on board the SS Lubeck, sailing from Sydney together with Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife. It was a propitious time. Brown was basking in the success of his Tongan mission and Stevenson was returning to Samoa where he had spent $4,000 (US) on a 314-acre jungle property named ‘Vailima’ in Apia, in 1889. Stevenson lived there happily for the last four years of his life and became known as ‘Tusitala, the Teller of Tales’. He retained the friendship of Brown, who was also fondly remembered by many of the local residents.

After a vote of thanks at the 1891 Mission Conference, Brown was able to relinquish his post as Special Commissioner to Tonga. He was saddened to hear the news of King George’s death in 1893 at the age of ninety-six, but British influence continued to be strong with his successor, his great-grandson, who became King George (III). In May 1900 the group became a British protectorate under the native flag.

Brown received an honorary doctorate from McGill University in 1892 and was and active member in the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science. He became a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. He continued to write prolifically both in his journals and correspondence and in many printed pamphlets and articles. He wrote notable pieces on language, science and ethnography, including ‘the ‘Conceptional theory of the origin of Totemism.” He corresponded with J G Frazer concerning such matters and Frazer replied:

“I feel that on all matters concerning savage custom and belief you have a far better right to express an opinion than I have. For I have lived all my life among books, you have spent most of yours among savages.”

Discussions about the possibility of a new mission to New Guinea had started at the Mission Conference of 1890, following a proposal by the Rev G Woolnough. Despite the presence of over 700 European miners on the eastern end of the island, there were no missionaries in that area and the London Missionary Society (LMS) had declined the opportunity to get involved. Woolnough’s proposal had the support of Sir William MacGregor, Governor of British New Guinea, and was approved by the Mission Board. Brown was instructed to visit New Guinea and he left Sydney on 18 May 1890, arriving in Port Moresby on 9 June.

The first difficulties that he had were with rival missionary organisations, as both the LMS and the Anglo-Australian Board of Missions (AABM) were now expressing interest in the same territories. As in most cases, all was resolved amicably with the LMS and AAMB carving up the mainland and the Wesleyans taking most of the islands. Brown then proceeded to explore the new missionary territories, maintaining his usual habit of recording ethnographical and scientific data as he went and collecting specimens. At Port Moresby he witnessed an interesting game being played by a group of local boys and girls on the beach. The girls started by linking arms and forming the shape of a ship. The boys stood distance away and raised branches above their heads and proceeded to make a hissing noise, imitating the wind. They then ran towards the girls with the object of breaking them apart and destroying the ship. This took several efforts and then roles were reversed.

Brown visited Mairu, Suau, Samarai, Basilaki, Slade, Bentley, Rossell, Woodlark and many other islands. They decided to establish the Mission base at Samarai, at the Eastern tip of British New Guinea, where there was a good port and a modest government residence. He also visited the Trobriand Island Group where he took a number of photographs. He noted the similarity between the local dialect and that of New Britain.

He returned to Sydney in August 1890 and presented his report to the Mission Board outlining the steps to be taken to develop the mission in New Guinea. His proposals were accepted and he went back to the islands on 27 May 1891. He was delighted with the progress that had been made, especially the construction of the mission houses on Samarai. He was also able to give the natives a lantern show, showing them the photographs he had taken the year before, and this caused great excitement. He issued instructions for the future development of the mission and then set sail for his old mission in New Britain on 14 July.

Brown was impressed with the pace of change in Matupit. Where he had landed on deserted beaches only 16 years before, he could now see a large wharf, coal sheds, stores and dwelling houses. When he visited New Ireland, he found it to be as safe as anyone could hope. He returned to Sydney on 6 September 1891.

His third visit to New Guinea was not until 1897, six years after the beginning of the Mission. On 10 June he noted in his journal:

“I have wandered about the station locating various points of interest, and comparing the present state with that of six years ago, when we first landed here. Then it was all wild bush; the first sound of the Gospel had not been heard in the land; the people were wild, dark, and ignorant, and they neither knew us nor the message we came to deliver. Today there is a beautiful station, well-kept gardens in front of all the houses, a good church, a small hospital, teachers’ houses, houses of students, nearly a hundred people resident on the station, boys and girls saved from a life of immorality and sin, students being prepared for the blessed work of preaching Christ to their own countrymen….”

He made a fourth visit to New Guinea in 1898 and a fifth in 1905 at the age of 70. Mr and Mrs Bronilow were still in charge of the Mission that he had founded and had recently completed a translation of the New Testament into the New Guinea language. By 1907, they had built 57 churches in the islands and had 19,776 regular worshippers, whilst in New Britain there were 155 churches and 19,594 regular worshippers.

Both later visits were linked with a secondary trip to the Bismarck Archipelago. In 1898 he also revisited his happy former home in Samoa and opened a large stone church in Satupa’itea, Savai’i. A huge feast followed this ceremony where they roasted 809 pigs.

Brown’s first proper visit to the Solomon Islands was in March 1880 in the company of Captain Ferguson, as has been described above. He did not return to the islands until 1899 when he called in to the islands en route from New Britain to Sydney on the Port Moresby. He went to several of the islands and found that natives and traders still fondly remembered Ferguson. At Ruviana he met the trader, Frank Wickham, who was very knowledgeable and willing to provide Brown with whatever assistance he required. The local tribes were less helpful and he noted in his journal:

“For some reason or other neither [Ingava – a chief] nor his people want missionaries to live here. I wish, however, that our Church would give us some opportunity of beginning Christian work amongst them….”

On Rendova he heard that 62 white men had been killed there in the last few years and head-hunting and cannibalism was rife. He was also struck by the ubiquitous skull-houses scattered around the islands, containing the remains of island ancestors. When many of the crew of the Port Moresby became ill, he had to head to Sydney. They arrived back on 19 August 1899.

The call for a Mission to the Solomon Islands came from some native islanders who were living in Fiji and had been converted to Christianity. At the General Conference of 1901 it was agreed to commence work “in such parts as may seem most desirable and practicable, and at the earliest possible time.” Brown was sent to reconnoitre the territory, leaving Sydney on 3 July 1901 on the Titus. He was now 66 and took his daughter with him. He was particularly impressed with the beauty of the region – as can be seen in his description of Marovo Lagoon:

“We were all amazed at the beautiful scene which presented itself to our gaze. It is absolutely impossible to convey any adequate idea of wondrous beauty of the lagoon. It commences at some islands lying to the south-east of New Georgia, running in a north-east direction about forty-five miles, in a direct line. The width varies from three to ten miles in the main portion of the lagoon, and then decreases to a narrow channel at the north-east end. The whole of the lagoon is studded with beautiful islands of varying sizes, all of which are wooded, the bright foliage contrasting very charmingly with the blue of the deeper parts of the lagoon and the brighter green of the shallow patches.”

The natives were not generally welcoming, however, and it was clear that the mission was going to have to proceed with caution. He reported back to Sydney on 28 August 1901. The Board appealed for volunteers to staff the mission and a great number came forward in Fiji and Samoa. They sailed for the Islands with Brown on the Titus, arriving in Ruviana on 23 May 1902. He noted “there was no active opposition from the chiefs or the people”, but “they did not receive us with any enthusiasm or cordiality.” He decided that they should establish a base, keep to themselves and let curiosity take over.

This ‘wait and see’ policy eventually paid dividends as he saw when he came back to the Solomons in 1905 and found that the Rev Goldie had established a thriving mission on Ruviana. By 1907, they had built 22 churches in the islands and had 5,050 regular worshippers.

In June 1907, after 21 years in office, he resigned as General Secretary at the General Conference in Sydney, but continued in his post until April 1908. His colleagues paid tribute to 48 years of missionary service as a missionary in Samoa, as the founder and pioneer of the New Britain Mission, as Special Commissioner to Tonga, and as the prime mover behind new missionary endeavours in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

He visited London in 1908 and published his autobiography with Hodder and Stoughton. This was followed in 1909 by Melanesians and Polynesians: their life-histories compared and described, and in 1911 he wrote a key report on the ‘Future of Australian Aborigines'. He returned to England again in 1913, aged 78, to attend the centenary celebrations of the Methodist Church.’ George Brown died at his home , Kinawanua, Gordon, on 7 April 1917. His was followed by his wife on 7 April 1923.

He left behind a magnificent record of his life and work.

- His wonderful collection of artefacts was purchased by the Bowes Museum in Barnard Castle, County Durham in 1924. These were sold to the University of Newcastle in 1954, who sold them again in 1974 to the National Museum of Ethnography, Osaka, Japan. Some of the artefacts remain in the UK at the British Museum and other institutions.

- His papers went to the Mitchell Library at the State Library of New South Wales and it is these that we have filmed – in their entirety.

I have already mentioned the ten substantial volumes of missionary journals, 1860-1871, 1874-1880, 1888-1890 and 1897. Supplementing these are seven letter books spanning 1865-1880, 1886-1890, and 1902-1909. These cover the whole range of his concerns from his interest in aboriginal rights to his involvement in the 1886 Indian and Colonial Exhibition. Correspondents include R H Codrington (1830-1922, Anglican priest and anthropologist who made the first systematic study of Melanesian society), Lorimer Fison (1832-1907, Wesleyan missionary in Fiji, 1863-84, and anthropologist), Sir James Frazer (1854-1941, British anthropologist, historian of religion and author of The Golden Bough), Ferdinand von Mueller (1825-1896, botanist and writer, Director of the Botanic Gardens in Melbourne) and Edward Tylor (1832-1917, Professor of Anthropology at Oxford, 1896-1909, and Head of the University Museum).

There are a further fifteen volumes of miscellaneous volumes of correspondence and papers including: Tongan Papers, 1842, 1881-1892; Letters from natives, 1870-1916; Scientific and ethnological papers, 1877-1917; Papers regarding Polynesian and Melanesian languages, 1882-1895; Penisimani - Samoan stories collected and partly translated by Brown, 1861-1870; and notebooks.

Brown was also a keen photographer and we include 1,287 photographs of the region and its inhabitants taken and collected by him when he returned to the islands in the 1880s to document life in Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Samoa. This constitutes “one of the largest and earliest photographic records of the Pacific.” (Jude Philp, Australian Museum).

We have also chosen to include both a final printed copy of his autobiography (1908) and the original manuscript of the same. In many cases, the manuscript copy provides a fuller account. Finally, we include an additional volume of letters, 1872-1916, a volume of anthropological notes and queries concerning the Pacific islands, 1879-1917, and an unattributed volume of South Seas reminiscences

The manuscript and photographic records of the Reverend George Brown enable us to see the Pacific islands as they were in the second half of the nineteenth century and will be of great interest to all those interested in Pacific Studies, Polynesian Culture and the relationship between the West and the indigenous peoples of Oceania.

Please click here for a map of the Pacific Islands

<back

|

|